Cumin from Turkey

Why this case study?

Why this case study?

The incidence of child labour in cumin production in Turkey is explicitly mentioned in among others the List of Goods produced by child labour of the US Department of Labour and on the child labour map of Anti-Slavery International

Approach case study

Conducted by the Fair Labour Association (FLA).

- In addition to desk-based research, FLA gathered field data from July 2-6, 2018, during the peak harvest season in the Konya and Afyon regions in Central Anatolia, where cumin is produced extensively. A Worker Demographic Profiling was undertaken to profile workers and existing labour practices. FLA surveyed 21 workers’ families covering 172 individuals involved in cumin production. 3 out of the 21 surveyed households were locals, and 18 were migrant families. In addition to the household survey, FLA interviewed representatives from 2 governmental organizations and 4 civil society organizations, 2 traders, 2 labour contractors, 7 farmers and 3 cumin exporters (suppliers).

- The research was conducted in a specific region and regarding specific supply chains. Other regions and supply chains may have other characteristics.

Scale, scope and severity of child labour

- In general, in Turkey most child labour is related to agriculture. Due to the seasonal nature of agricultural work throughout the country, farmworkers often migrate with their families for up to seven months per year. Besides cotton, hazelnuts, citrus fruits, sugar beets, peanuts, apricots, melons, cherries and pulses cumin is one of the commodities falling in the circle of seasonal agriculture migratory work. Hired labour is required during weeding and harvesting periods. Farmers prefer hiring temporary workers if their production area is large or if they do not have enough labour force within their own household.

- Turkey has ratified ILO Conventions on Child Labour 138 and Worst Forms of Child Labour 182. As per the local legislation, work of children below the age of 15 years is considered ‘Child Labour’ and all work of children under the age of 18 years involved in seasonal migratory labour is considered ‘Worst Forms of Child Labour’. The research showed a high prevalence of child labour in cumin under 15 years of age (39.7%). In total 50.2 % of the working population is under 18 years old. 59 out of 100 surveyed children were found to be actively working in cumin harvest (see table). Of the 59 working children and young workers, 27 are male and 32 are female.

Distribution of working children in age groups (n=59)

| Working in cumin | Surveyed childen | Percentage | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age Group (years) | 0-4 | 0 | 15 | |

| 5-11 | 14 | 33 | 42.5% | |

| 12-15 | 32 | 37 | 86.5% | |

| 16-18 | 13 | 15 | 86.6% |

- 53.4% of the people amongst the working population (116) were illiterate. Illiteracy rate is higher for female workers. Of the 59 working children (under 18 years of age) who are in the school going age, 30 are illiterate and 28 are literate (1 worker was 6 years old and under the school going age). Among the working children and young workers, 28 have never attended school, 25 are currently students in elementary and high-school. The rest have dropped out of school.

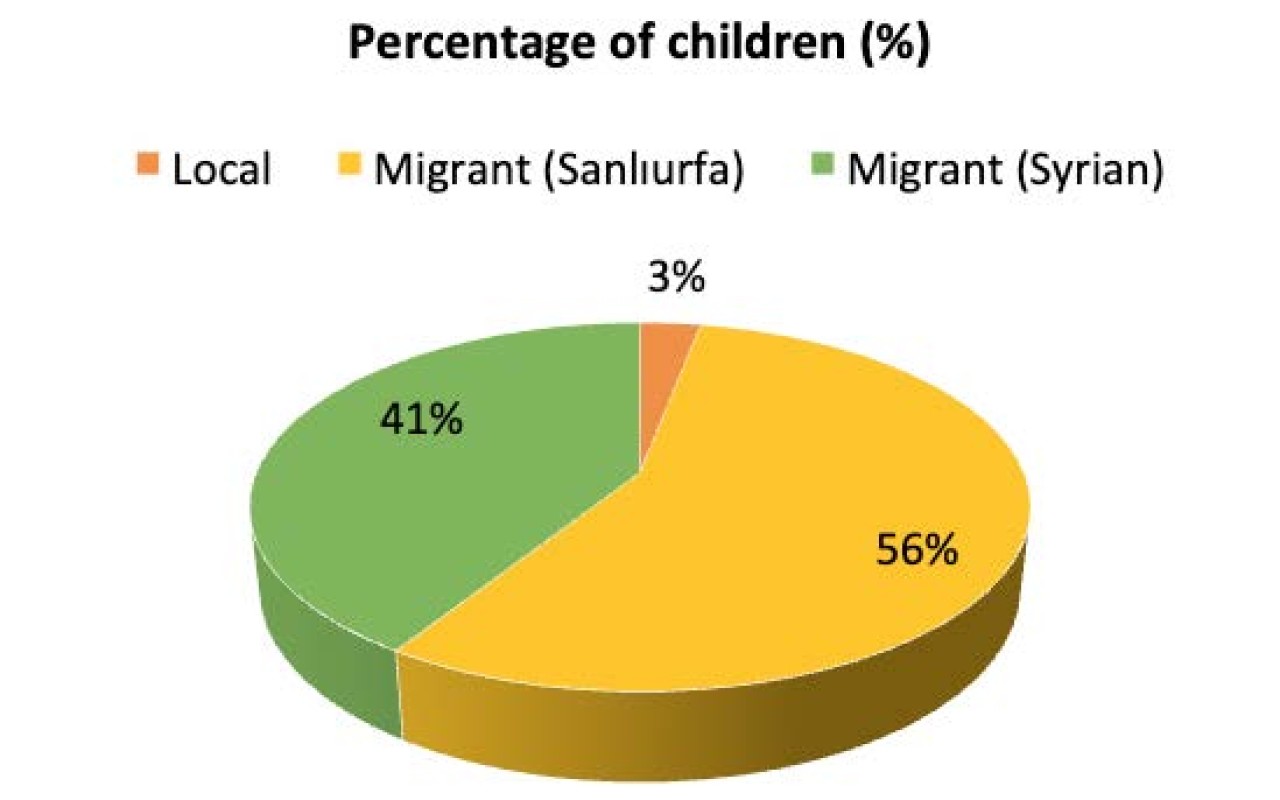

- Two types of workers can be distinguished: local workers and seasonal migrant workers. Seasonal migrant workers are mostly families from the South-Eastern part of Turkey and Syrian refugees. 97 out of 100 children surveyed belonged to seasonal migratory agricultural communities, while 3 of them belong to local communities (see figure).

- All interviewed seasonal workers stated that they work with a labour contractor, who arranges work, transportation from hometown and also mediates between the farmer and the workers on working conditions and compensation. It is common for seasonal migrant workers to borrow money from the labour contractor in order to pay for their expenses. In return for the services, labour contractors deduct intermediary commission from the workers’ earnings, which is generally set at 10% of the total earnings.

- The total working hours of both local and migrant workers fall in the range of 63 to 77+ hours per week. This also applies to children. This is way beyond the legal limit of 45 working hours per week for any type of work.

- Working conditions in the cumin fields are often harsh. Children are exposed to the same risks as they are actively contributing to weeding and harvesting activities. The farms are mostly located on dry and huge lowlands without any shade. In July, during summer, Konya and Afyon regions experience very high temperatures. One of the risks to workers’ health during this harvesting period is sunstroke and dehydration. Given the lack of shaded areas in the farms, the workers are not able to take a break from the heat. They must rely on caps and full sleeves clothes to protect themselves. Additionally, since the land is arid, dust levels are very high and this may adversely affect workers respiratory system and eyes due to long-term exposure. There are no toilets and running water on the farms. Workers have to carry their own water and food. The cumin plants have thorns that are harmful for the hands of the workers. Proper gloves must be used.

- Workers surveyed did not report they have received any trainings or awareness sessions on any topics (health & safety, good agriculture practices, labour rights, agronomics etc.) at the farms.

- Children involved in seasonal migratory agriculture work also face poor living conditions. In general, the camps or the places where they reside in the farms have poor sanitary conditions with limited access to potable water and electricity. In addition, since workers are not familiar with the cities they work in, they do not have their own transportation and they live far from the city, they cannot easily access healthcare services.

- Many migrant families work without registration and social security.

Key root causes

- In general, the socio-economic status of migrant families and Syrian families is very low. Most of them state they can barely subsist on the money they earn from agriculture. Many of them have debts and very few receive social aid. 90% of the households reported that their income is not enough to meet basic needs. Consequently, all family members, including children, need to work to maximize income. Cumin does not provide them with a living wage. On the contrary, workers are not even paid the legally mandated minimum wages or benefits. Local workers earn 50 Turkish Lira (TRY) (approx. Euro 6) per day, which is below the daily equivalent of minimum wage in Turkey. Migrant workers receive lump sum payments calculated according to the acre of the cumin they harvest. The price per acre varies between TRY 60- 80 depending on the negotiated terms between the farmer and labour contractor. Labour contractors deduct 10% of the total earnings. In the end, seasonal migrant workers only earn TRY 40-55 per day. Children were reported to be paid half of the adult wages, yet in some cases, farmers may decide to pay the children the adult wages if they work efficiently.

- None of the surveyed workers reported presence of a day care or other child care facilities where they can place children when they go to the farms. Hence they have no other option than bringing their children with them.

- The camp areas where migrants live are usually far from the city and town centres and there is no transportation opportunity. Hence, it is difficult for children attending school.

- Farmers tend to hiring entire families given that they need a lot of workforce within a very short harvesting period. They are under increasing pressure to harvest due to changing climate.

- To be able to supply high volumes, Turkish suppliers tend to source from multiple parties such as directly from farmers, farmer cooperatives, local markets, wholesalers and other smaller companies. Hence, a 100% traceable supply chain is difficult unless a supplier is exclusively producing and processing cumin grown on its own farms. A second layer of complexity in knowing the upstream supply chains is when cumin is bought in Syria and sold through the companies or traders based in Turkey.

- Suppliers and traders may raise concerns if increased costs for enhanced labour and living conditions of workers and better traceability cannot be compensated by higher cumin prices.

- Local administrations may convey their concerns about that they do not receive enough support and funding from the central government to improve living and working conditions of the workers- such as providing proper camp areas, training center for the children etc.

|

Given that almost 50% of the current workers population are children, it will be difficult to replace all of them immediately in a short term. It may also have counter-productive consequences if the income of the households is not maintained. Remediation therefore requires careful thinking and planning and funding over a period of 3-5 years. A short, medium- and long-term remediation and mitigation strategy needs to be developed that will improve the current child labour situation, provide a decent living to the families and enhance the working and living conditions of the workers. Dutch spice companies and their Turkish suppliers cannot achieve this alone and they will need to work with a number of key partners. There are however some actions that both the Turkish suppliers and the Dutch companies can take in the near future and which are under their sphere of influence. |

Proposed mitigating measures by Turkish suppliers

FLA recommends Turkish suppliers to:

- Assign a responsible person to develop, implement and monitor responsible sourcing programs.

- Develop an internal monitoring program that stipulates how to monitor and collect data, to engage with farmers, to communicate their requirements to the farmers, to gain their loyalty and to start a dialogue with them on how to address the issues of age verification, practices of labour contractors, and payments.

- Increase of transparency in the supply chain with a stronger focus on traceability.

- Put in place annual target and key performance indicators related to responsible sourcing programs.

- Together with downstream supply chain actors (intermediaries) to launch awareness raising and training programs on child labour and labour rights (compensation, working hours, employment relationships, health and safety) to target both farmer and seasonal migrant worker communities. Ensure that workers are informed about the terms and conditions of their employment and their rights issued in a proper contract by the labour contractors or farmer, that workers are paid at least minimum wages according to national laws, that they work reasonable hours and have reasonable production quotas.

- Deploy occupational health and safety experts during the cumin harvest across the entire region and arrange trainings by these experts to both farmers and workers.

- Develop a comprehensive program to target labour intermediaries’ capacity and awareness through formal and practical trainings in order to improve both working and living conditions of seasonal migrant workers. If labour intermediaries capacity increases, they can demand decent living conditions to be provided by the employer (field and orchard owners) and relevant public bodies and organisations.

- Engage with local governorates, municipalities, local directorates of Ministry of Agriculture, and Chamber of Agriculture to improve infrastructure (electricity, water, sanitation facilities - toilets, cooking facilities rest and recreation) for workers living in harvest regions to ensure minimum standards of hygiene and decent living conditions.

-

Establish user-friendly, easy-to-access grievance and feedback mechanisms that would bring workers into direct contact with companies and also public authorities and private actors.

- Cooperate with farmers to increase the implementation of good farming practices that would increase productivity.

- Other than labour intermediaries, private employment agencies can be another option to recruit agriculture workers since the employment terms are clear and more feasible to monitor. Especially farmers are integral part of the programme, their participation in decision making and programme development is crucial. Farmers should be involved maintaining responsible sourcing programmes and trainings on fair labour practises.

- Suppliers and spice companies can communicate with government bodies and related local administrations to reach solutions for corrective actions, especially to get support what can be done for the living conditions in the camp areas, such as providing running water, toilets etc. Create projects on WASH (Water, Sanitation and Health), improving working conditions in the region. Implementation strategies should be built around public-private partnership initiatives and multi-stakeholder collabourations.

- Specific intervention on the Child Labour Free Zone (CLFZ) will need to be adapted for seasonal migrant labour as these workers are mobile. CLFZ and other area-based approaches are more applicable with populations that experience localized issues. Nevertheless, components of the CLFZ such as interface with the authorities on the access to schools, or provision of the child friendly spaces can be adopted.

Proposed measures for Dutch spices companies

The FLA recommends international (downstream) buyers to

- Develop or/and revise a Supplier Code of Conduct to regulate buying and production practices for the cumin sector. This code should include labour and environmental standards. Standards specific to Turkey related to the seasonal migrant cumin workers should be added as an annex to the overall code.

- Include the standard as part of the Supplier Contracts and the supplier should cascade the standards all the way down to the farm level. It is important that the suppliers and the companies have the same understanding of the various clauses of the standards. For example, what is meant by supply chain traceability or child labour. It is important to not just treat the Code of Conduct as an administrative document, but a document to engage in dialogue with suppliers.

- Set goals for supply chain mapping and traceability targets and ask suppliers to increasingly disclose the location of the farms to the companies so that if required companies can conduct monitoring exercise. It is recommended that foreign spice companies facilitate the supplier to conduct supply chain mapping and train them in monitoring labour standards. Finally, monitor the application of the standards throughout the supply chain.

- Set annual targets along with key performance indicators related to responsible sourcing programmes. These indicators should be monitored to ensure progress towards the goal of compliance.

- Launch a technical support and capacity building program for suppliers by setting clear guidelines on the aim of the program, how to monitor cumin production fields in collabouration with other stakeholders and create action plans. Provide tools to the suppliers, build their capacity and conduct joint farm visits with them to take stock of the situation.

- Reserve a budget (e.g. a proportion of their annual revenue (0.01-0.03 %) related to cumin production in order to support supply chain actors improving working conditions of seasonal agricultural workers and eliminate child labour. The following are some activities for which this fund could be used:

- building of temporary decent accommodation units/living quarters for seasonal agricultural workers during the cumin harvest. Utilities such as electricity, clean water, sanitation and safety of their living spaces can be improved in collabouration with local authorities, municipalities, suppliers and farmer organizations. Companies need to engage with local governments to pull the METIP resources in harvest regions.

- providing personal protection equipment (PPE) to workers.

- supporting establishment of child friendly spaces, child care facilities play and sports centers, and summer schools in selected areas in collabouration with local authorities and NGOs to keep children away from cumin farms.

- contributing of a portion of the social security premiums of the workers in order to ensure that workers are covered under social security.

- Support the establishment of or join an existing multi-stakeholder multi-sectoral round table for the agricultural sector in Turkey to join forces with peers.